MIT professor of physics Richard Milner, Jefferson Laboratory physicists Rolf Ent and Rik Yoshida, MIT documentary filmmakers Chris Boebel and Joe McMaster, and Sputnik Animation’s James LaPlante have teamed as much as depict the subatomic world in a brand new approach.

An art-science collaboration checks the bounds of visible applied sciences.

Attempt to image a proton — the tiny, positively charged particle inside an atomic nucleus — and it's possible you'll envision a well-recognized, textbook diagram: a bundle of billiard balls representing quarks and gluons. From the strong sphere mannequin first proposed by John Dalton in 1803 to the quantum mannequin put ahead by Erwin Schrödinger in 1926, there's a storied timeline of physicists trying to visualise the invisible.

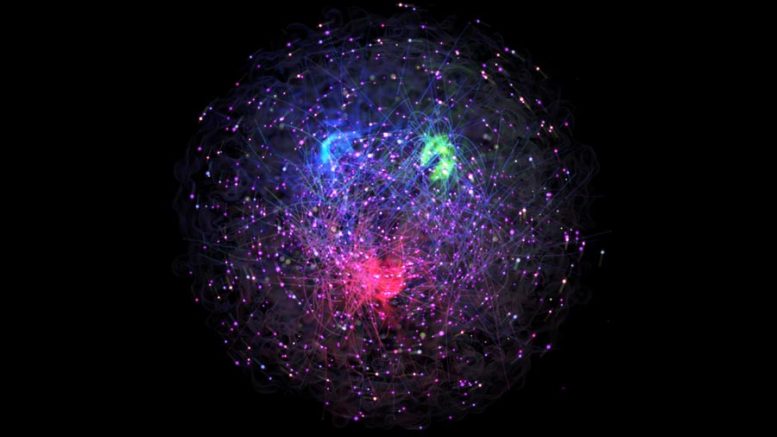

An revolutionary animation conveys the present understanding of the construction of the proton. Credit score: James LaPlante/Sputnik Animation

Now, MIT professor of physics Richard Milner, Jefferson Laboratory physicists Rolf Ent and Rik Yoshida, MIT documentary filmmakers Chris Boebel and Joe McMaster, and Sputnik Animation’s James LaPlante have teamed as much as depict the subatomic world in a brand new approach. Offered by MIT Middle for Artwork, Science & Expertise (CAST) and Jefferson Lab, “Visualizing the Proton” is an authentic animation of the proton, meant to be used in highschool lecture rooms. Ent and Milner introduced the animation in contributed talks on the April assembly of the American Physics Society and in addition shared it at a neighborhood occasion hosted by MIT Open House Programming on April 20. Along with the animation, a brief documentary movie concerning the collaborative course of is in progress.

Visualizing the Proton.

It’s a mission that Milner and Ent have been fascinated by since at the least 2004 when Frank Wilczek, the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at MIT, shared an animation in his Nobel Lecture on quantum chromodynamics (QCD), a concept that predicts the existence of gluons within the proton. “There’s an enormously sturdy MIT lineage to the topic,” Milner factors out, additionally referencing the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded to Jerome Friedman and Henry Kendall of MIT and Richard Taylor of SLAC Nationwide Accelerator Laboratory for his or her pioneering analysis confirming the existence of quarks.

For starters, the physicists thought animation could be an efficient medium to elucidate the science behind the Electron Ion Collider, a brand new particle accelerator from the U.S. Division of Power Workplace of Science — which many MIT school, together with Milner, in addition to colleagues like Ent, have lengthy advocated for. Furthermore, nonetheless renderings of the proton are inherently restricted, unable to depict the movement of quarks and gluons. “Important components of the physics contain animation, shade, particles annihilating and disappearing, quantum mechanics, relativity. It’s virtually unimaginable to convey this with out animation,” says Milner.

In 2017, Milner was launched to Boebel and McMaster, who in flip pulled LaPlante on board. Milner “had an instinct that a visualization of their collective work could be actually, actually worthwhile,” recollects Boebel of the mission’s beginnings. They utilized for a CAST school grant, and the workforce’s concept began to come back to life.

“Visualizing the Proton” is an authentic animation of the proton, meant to be used in highschool lecture rooms. Credit score: Animation courtesy of the “Visualizing the Proton” workforce

“The CAST Choice Committee was intrigued by the problem and noticed it as an exquisite alternative to focus on the method concerned in making the animation of the proton in addition to the animation itself,” says Leila Kinney, government director of arts initiatives and of CAST. “True art-science collaborations are extra complicated than science communication or science visualization tasks. They contain bringing collectively totally different, equally refined modes of creating inventive discoveries and interpretive selections. You will need to perceive the probabilities, limitations, and decisions already embedded within the visible know-how chosen to visualise the proton. We hope folks come away with higher understanding of visible interpretation as a mode of important inquiry and information manufacturing, in addition to physics.”

Boebel and McMaster filmed the method of making such a visible interpretation from behind the scenes. “It’s at all times difficult while you deliver collectively people who find themselves really world-class consultants, however from totally different realms, and ask them to speak about one thing technical,” says McMaster of the workforce’s efforts to supply one thing each scientifically correct and visually interesting. “Their enthusiasm is absolutely infectious.”

In February 2020, animator LaPlante welcomed the scientists and filmmakers to his studio in Maine to share his first ideation. Though understanding the world of quantum physics posed a novel problem, he explains, “One of many benefits I've is that I don’t come from a scientific background. My objective is at all times to wrap my head across the science after which determine, ‘OK, properly, what does it seem like?’”

Gluons, for instance, have been described as springs, elastics, and vacuums. LaPlante imagined the particle, thought to carry quarks collectively, as a bath of slime. For those who put your closed fist in and attempt to open it, you create a vacuum of air, making it tougher to open your fist as a result of the encompassing materials desires to reel it in.

LaPlante was additionally impressed to make use of his 3D software program to “freeze time” and fly round a immobile proton, just for the physicists to tell him that such an interpretation was inaccurate primarily based on the present information. Particle accelerators can solely detect a two-dimensional slice. In reality, three-dimensional information is one thing scientists hope to seize of their subsequent stage of experimentation. That they had all come up towards the identical wall — and the identical query — regardless of approaching the subject in completely alternative ways.

“My artwork is absolutely about readability of communication and making an attempt to get complicated science to one thing that’s comprehensible,” says LaPlante. Very like in science, getting issues fallacious is commonly step one of his creative course of. Nonetheless, his preliminary try on the animation was successful with the physicists, they usually excitedly refined the mission over Zoom.

“There are two fundamental knobs that experimentalists can dial after we scatter an electron off a proton at excessive power,” Milner explains, very like spatial decision and shutter pace in pictures. “These digital camera variables have direct analogies within the mathematical language of physicists describing this scattering.”

As “publicity time,” or Bjorken-X, which in QCD is the bodily interpretation of the fraction of the proton’s momentum carried by one quark or gluon, is lowered, you see the proton as an virtually infinite variety of gluons and quarks shifting in a short time. If Bjorken-X is raised, you see three blobs, or Valence quarks, in pink, blue, and inexperienced. As spatial decision is dialed, the proton goes from being a spherical object to a pancaked object.

“We expect we’ve invented a brand new device,” says Milner. “There are fundamental science questions: How are the gluons distributed in a proton? Are they uniform? Are they clumped? We don’t know. These are fundamental, basic questions that we will animate. We expect it’s a device for communication, understanding, and scientific dialogue.

“That is the beginning. I hope folks see it world wide, they usually get impressed.”

Post a Comment